At age 26, recently engaged and about to start my first grown-up managerial position in city government, I was handed a hefty report summarizing the results of my “comprehensive executive health assessment,” an onboarding requirement for all the city’s newly hired managers. The process had included an extensive physical examination, a lengthy written questionnaire, and an hourlong in-person interview with a nerdy, non-smiling white guy who took detailed notes on my diet, lifestyle and mental health.

I relaxed immediately when I saw I had received an overall rating of “excellent health.” Then I turned to the last page of the report and read some alarming news. If I were to die in the next year, the report informed me, the likeliest cause of death would be homicide.

The next day, my first call was to Mr. Non- Smiley.

“Hey, I got my health assessment,” I began, trying to sound managerial and calm while feeling anything but, “and I have a few questions. Since I was found to be in excellent health, I was a little surprised to learn about my risk of being murdered. Do you know something I don’t know?”

“Well, first, Miss Belk, let me just say we are very objective,” he replied in a dry monotone. “It’s all about data and the model.”

“OK, so why did the model conclude that I’m at risk of being killed?”

“You’re an otherwise healthy African American woman between the ages of 21 and 30. The data show that if you were going to die today, it would likely be the result of a homicide.”

“So, what’s that about? My age, my race, my gender?”

“Oh, race by far,” he said quickly. “If you were white, it would likely be some type of accident. Car, probably.”

The “it” part — the likely cause of death; in my case, homicide — jarred me. Silence. Mr. Non-Smiley, breaking the silence, and finally showing a little compassion in his own awkward way.

“You know, Miss Belk, it’s only data. Besides, once you make it to your 30s, heart disease, stroke and cancer kick in as key data points.”

I did make it to 30. But my big sister, Vickie, and cousin Darryl didn’t. They both were murdered, victims of gun violence in their 20s.

Neither of us knew it at the time, but Mr. Non-Smiley had given me my first lesson in what public health professionals call “the social determinants of health,” a fancy way of saying that your income, ZIP Code and race can and often do determine your health, longevity and even your cause of your death.

What I know now is that the long history of racial discrimination in our country has led not only to economic disparities but to poorer health outcomes for black people.

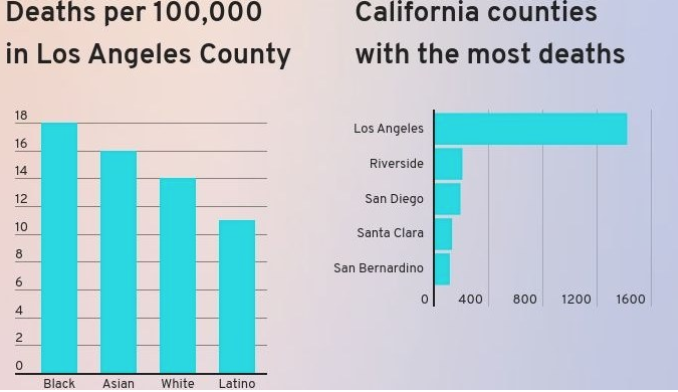

Consider what’s happening right now with the coronavirus. In cities across the country, COVID-19 is disproportionately affecting black and brown communities.In Louisiana, black people account for 32% of the population but 56% of the COVID-19 deaths. In Chicago, black people account for about 55% of the deaths, but only about a third of the population. Americans have lived with this kind of data for a long time, on disease after disease. It’s about time we did some new modeling where racial equity is front and center.

Source: -cont- https://www.calwellness.org/stories/its-no-surprise-black-and-brown-communities-are-hit-hard-by-covid-19/